In November 2016, tipped off by a ‘partner organisation’ advising that an ‘APT actor’ had gained administration access to a fourth-tier defence contractor, ASD and CERT Australia were rapid to respond and on site the following day. Though on arrival, without official ASD credentials, the ‘customer’, a small aerospace engineering firm, with about 50 employees, called into question the bona fides of these ‘visitors’ from the Federal Government. Even calls to the CERT Australia Hotline did not initially verify the visit. Yet despite this and with the best social engineering techniques at play, they were able to later walk out with hard-drives of historical backups, in order to commence an official forensic investigation.

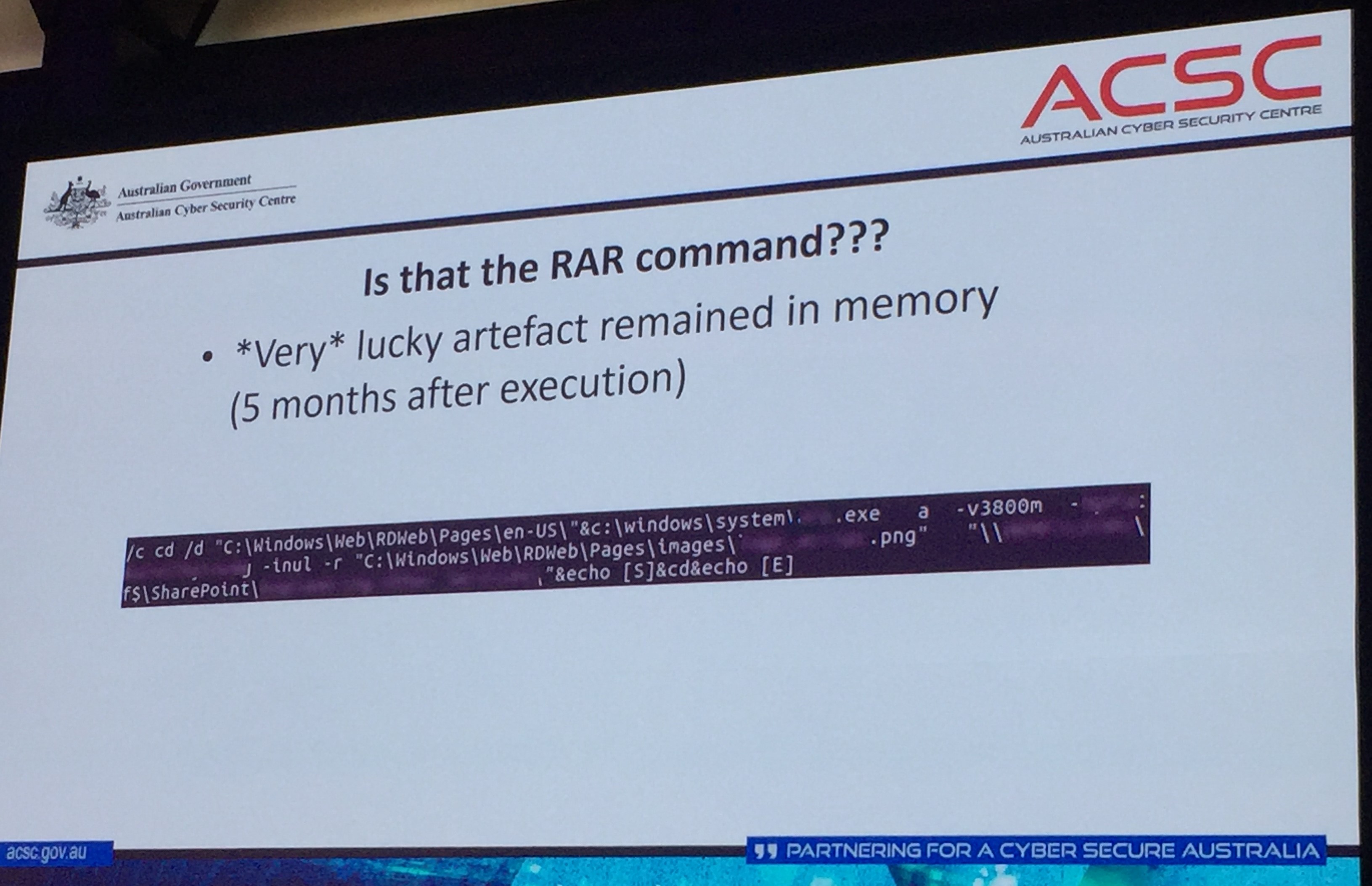

The investigation revealed the company had been compromised five months earlier, in July 2016, and involved a significant amount of data being stolen, and most was defence related, including data related to the Joint Strike Fighter program and other primary defence hardware.

The investigation revealed the company had been compromised five months earlier, in July 2016, and involved a significant amount of data being stolen, and most was defence related, including data related to the Joint Strike Fighter program and other primary defence hardware.

Step one involved gathering the Executives and IT Staff…of which there was one…together in a room and advising them they had been seriously compromised and yet “it was no one’s fault.”

“The fact you have valuable information, you would have likely been breached either way and let’s focus on treating the problem. Too many organisations seek to apply blame and this isn’t helpful,” said the ASD Incident Response Manager, presenting to a full conference room in Sydney at #AISACON17.

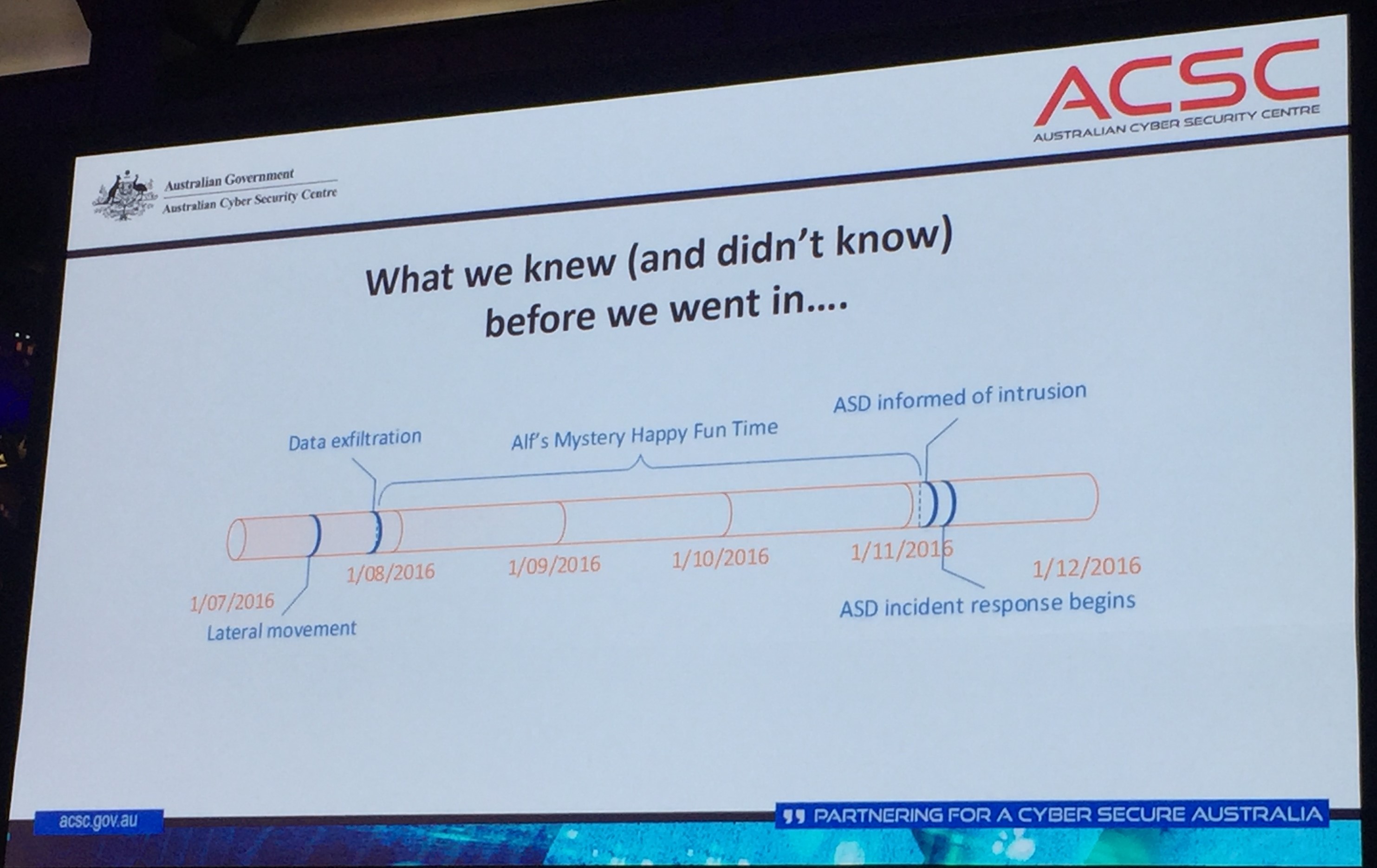

One may beg to differ. Blame could be easily attributed to the Executives who allowed this small self-managed network to be supported by one IT person, and without a security risk assessment, which would have highlighted the vulnerabilities involved with using a common local admin account, no DMZ, no regular patching regime, and with hosted internet facing services…all whilst handling defence data and commercially sensitive information. In this case, because of the defence data, the investigation became a combined ASD and CERT Australia investigation.

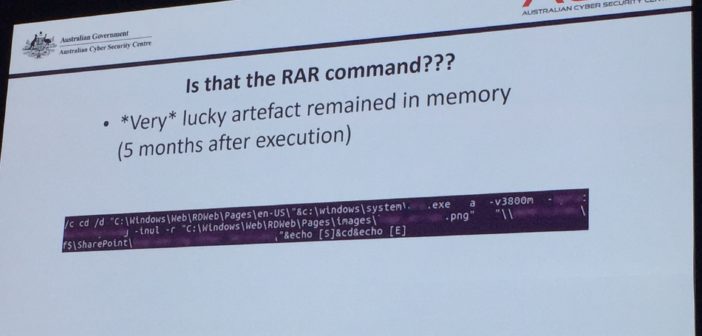

It was a current and historical compromise. ASD deployed host based agents to the end points, Google Rapid Response (GRR) and Carbon Black to commence recording module loads, file modifications, to record what was happening in the environment. Investigators seized the server backups and related domains. ASD established an Exfil host on the remote desktop server and had hoped to just review the access logs and seek out a foreign IP address. That was not the case but they did find a China Chopper web shell, a recognised and popular stealth access tool, commonly used by Chinese cybercriminals (1) and WinRAR, a data compression tool. The analysis determined about 30GB of defence and commercially sensitive data had been accessed and downloaded.

A key learning outcome was that companies, particular defence contractors, need to become more granular on the type of security controls required. The techniques used by the APT Actor was not real tradecraft, instead just leveraged poor network configurations. The IT helpdesk server was vulnerable with internet access, single factor authentication, was unpatched and had a CVE via Metasploit. The vulnerability was easily executed but turned out wasn’t actually required, as a default username and password was still being used. ASD stated they realised this exploit was actively used against multiple Australian companies and the time difference between scanning and exploit was about 7 days, suggesting a nation state actor who was slow and deliberate.

Once access had been gained, the APT Actor ran tools to collect credentials and ultimately gained full access, to the entire network. This access included reading emails of the company’s engineers, finance controllers and operational managers, and logging into all servers, including accessing CAD systems and company documents, touching all points inside the environment.

Once access had been gained, the APT Actor ran tools to collect credentials and ultimately gained full access, to the entire network. This access included reading emails of the company’s engineers, finance controllers and operational managers, and logging into all servers, including accessing CAD systems and company documents, touching all points inside the environment.

The case study highlights ASD recommendations to disable local admin accounts and deploy password solutions, including two-factor authentication, to ensure each machine in the environment has a unique and regularly changed password. Reduced privilege reduces risk.

ASD confirmed attribution is getting more difficult but nor is it always the goal. The response involved ensuring they get the Actor off the network and stop further access.

“Cyber espionage is professionalising,” said ASD, “capability is in people not tools. Invest in people and build the workforce.”

With the increasingly workloads, confirmed in the ACSC Threat Report 2017, ASD is continuing to recruit.

It is clear from this case study, that further and continued education is needed, not just technical training but educating company executives that they have a fiduciary duty to ensure they assess the risks and recognise ‘security’ is not to be assumed or disregarded.

Chris Cubbage, Executive Editor